This article is cross-posted with American Pianists Association’s Beauty of Music, a regular feature on the American Pianists Association blog that covers variety of topics to help readers better understand and appreciate the music they love. Sign up for 88 Keys, the monthly newsletter of the American Pianists Association, to automatically receive each issue.

I was fortunate four years ago to be selected as the winner of the American Pianists Awards, becoming a Christel DeHaan Classical Fellow for the following four years. The competition was a year-long process, which included performances with the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, Indianapolis Chamber Orchestra, the Linden Quartet, and soprano Jessica Rivera. It was one of the most amazing musical experiences of my life! I also got to hang out with my fellow finalists, most of whom I was already friends with, and get to know the amazing arts community of Indianapolis.

Apropos to the concert Nikita Mndoyants will be giving for APA’s Grand Encounters, we will be talking about Liszt’s paraphrase of the overture to Wagner’s Tannhäuser. It is a piece that I have worked on as well, both in Liszt’s form, as well as in the original form when I was a violinist in the Conejo Valley Youth Orchestra. I am so grateful that we tackled this piece in youth orchestra, because I got to know this piece intellectually and emotionally before I ever set out to learn the transcription. The scrubbing and woodshedding I had to do, both on the violin and on the piano, for this piece will never be forgotten.

For your enjoyment while reading, here’s a recording from when I played this overture in a recital for the 2015 Cleveland Young Artist Competition as a guest artist.

Transcription, Arrangement, Paraphrase – what’s the difference?

Liszt used many words: phantasie, paraphrase, transcription, reminiscence, …sur de[s] [themes/motifs de] … , d’après, illustrations, etc. to describe his arrangements. I think you can tell to what degree of freedom Liszt is going to take his arrangements by the words he uses. It seems that transcriptions and paraphrases (and any which just bear the title of the original work) are his most true-to-the-source works.

Transcriptions exist not only in music, but in literature and spoken word as well. If you break down the word transcribe, it is literally “across-write” in Latin, and it implies writing or copying across different forms of media. In language, transcription is more akin to recording – you often get transcripts of speeches printed in papers or news sites. Transcription is also used in biochemistry, describing the creation of RNA from DNA. The “language” of DNA and RNA are very similar, but not quite, and so transcription seems to be a fitting word.

Arrangement is very similar to transcription – it usually means taking a piece and rewriting it for a different instrumentation. My inclination is to consider transcriptions to be more faithful and also more technically demanding than arrangements, which often tend toward simplification or for mass consumption.

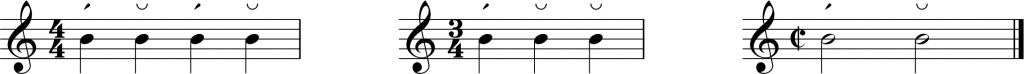

Then what about paraphrases? In language, paraphrases are a rewording or approximate copy of something previously written or said. In music, paraphrases might be more flexible with material added in or taken out. Or they may have figurations that are completely changed, or in the case of the Tannhäuser Overture, meters altered. I don’t think Liszt would have really dared to do too much of that with the Beethoven Symphonies, for example.

Transcription as Translation

Another trans- word we should mention is translation. Transcription in musical terms is rather like translation, but instead of moving between languages, it is moving between instrumentation. This seems like a pretty obvious connection, but it becomes even more robust once we get beneath the surface. In any translation of text, there is always the consideration of how literal should the text be. If the translation is too literal, the translator runs the risk of losing high level meanings, such as idioms or figures of speech. On the other hand, if the translation is too free or stylized, the original meaning could be lost, as could cultural-specific ideas.

In transcription of music, these considerations are also important – there are certain passages or chords that can be played in one instrumentation that are impossible on another. The trouble is finding how to make it work on the new instrumentation in a way that is idiomatic, but at the same time retains the essence of the original (whatever the transcriber decides that may be). Furthermore, even the structure of phrases or large chunks of material may be altered to make the music more effective on the destination instrumentation.

The signature of a transcriber lies in how they deal with these challenges. Pianists and music lovers will be familiar with the different ways the details of transcription occur between arrangements by Liszt, Busoni, Godowsky, or Rachmaninoff, etc. It’s the fingerprint not only of their pen and hands, but also of their ears.

Konzertparaphrase

Either Liszt or his publisher titled this piece as a “concert paraphrase” and so we have to consider a bit what this means. Surely, compared to his “Réminscences” this piece is very faithful. However, compared to works like his arrangement of the Beethoven Symphonies, this piece might be considered ever so slightly less strict in its transcription.

I would say the baseline for this piece is a very straight-forward transcription of the orchestral version. For example, the opening wind chorale works very well as is on the piano. Even a lot of the string figurations are pretty much unaltered. But with that out of the way, we can start to see both the subtle and not-so-subtle changes that Liszt makes, and try to see why he made them.

Voice Leading on the Piano

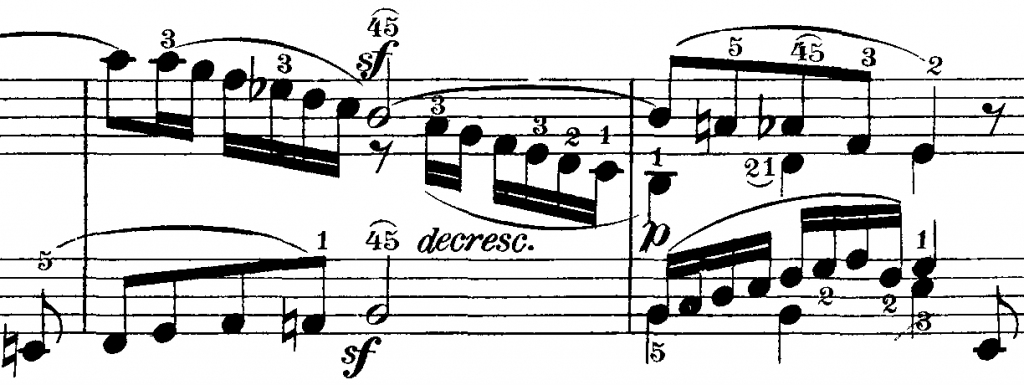

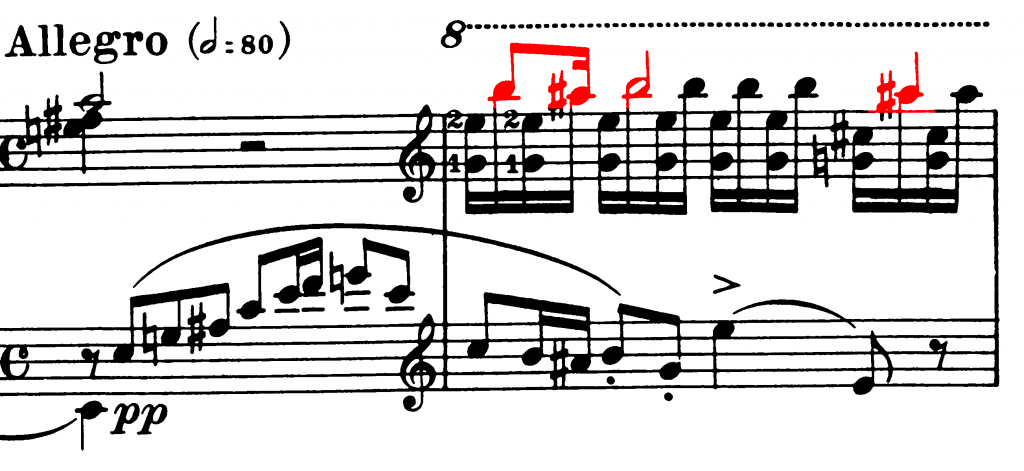

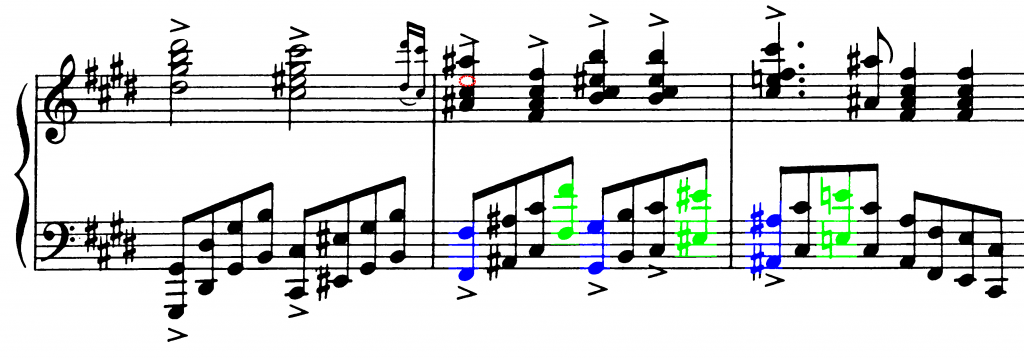

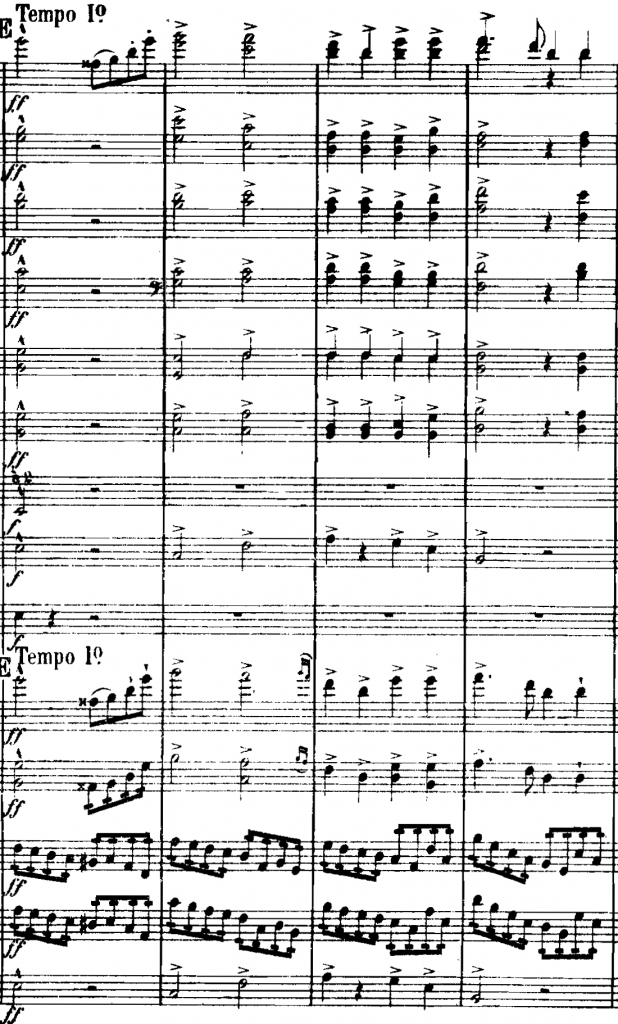

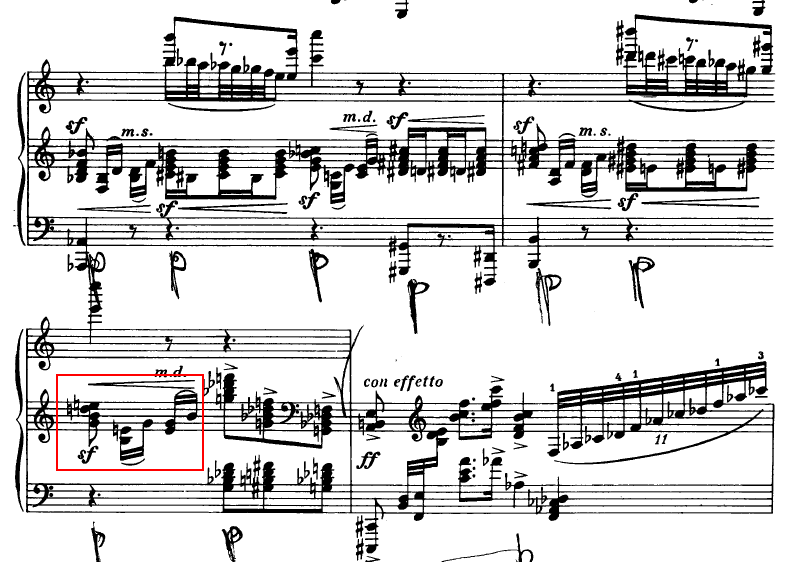

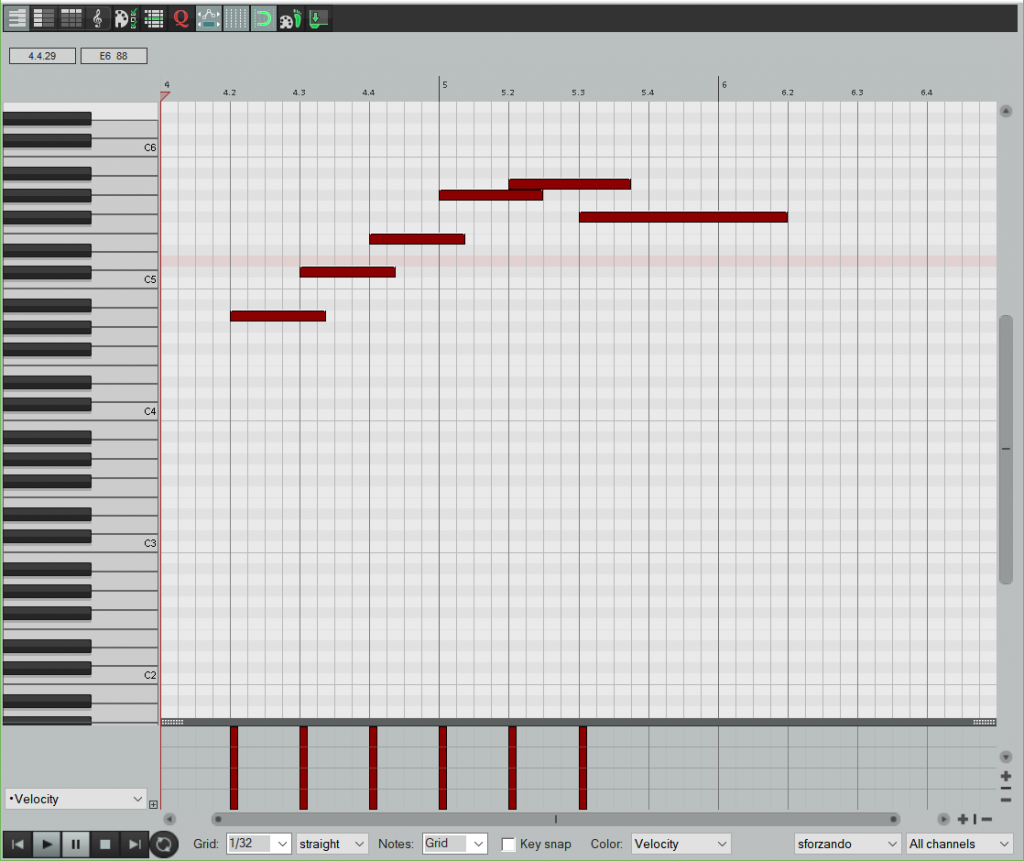

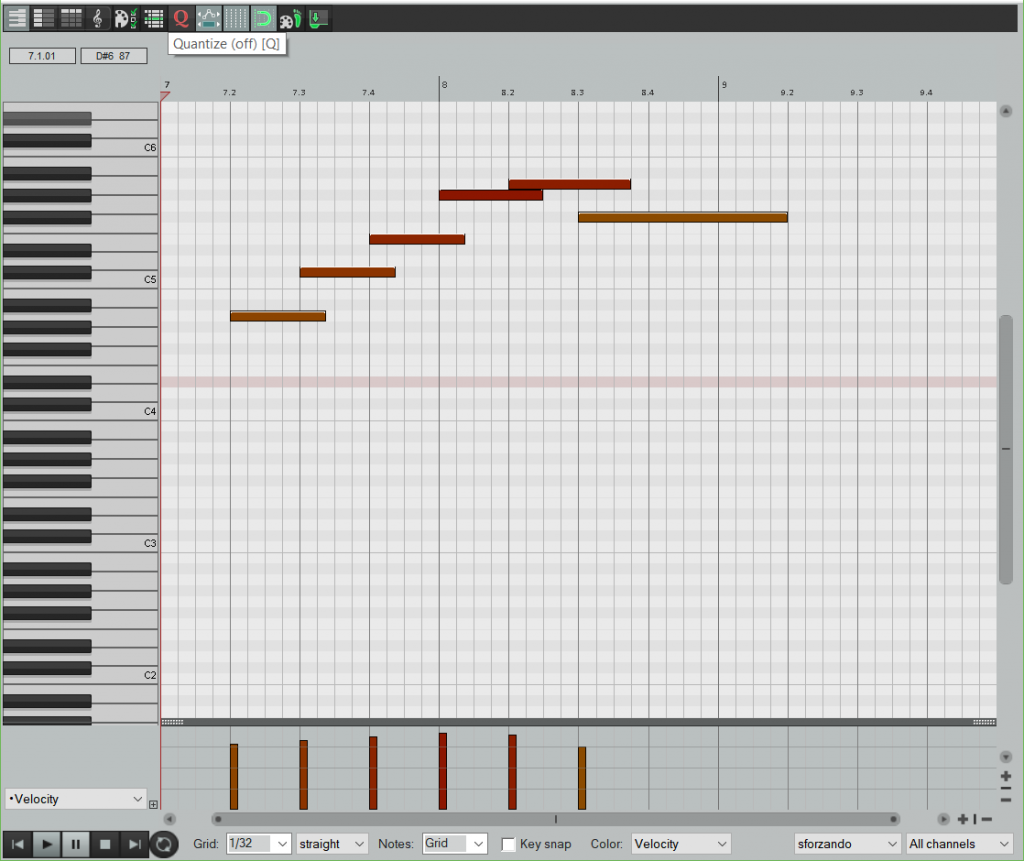

I mentioned previously that the wind chorale in the beginning is mostly the same. The changes are minute, but interesting. Liszt adds some extra notes to make the voice leading work a bit better on the piano – the doublings in the orchestral version would cause some texture inconsistencies if transcribed exactly:

When played by multiple instruments, doubled notes sound doubled. But on the piano, when two voices collapse to a unison, the audience rarely hears it as such, and it sounds more like a voice has dropped out. I would argue this is the reason why Liszt has made the changes above.

The opposite can also be true – sometimes Liszt will leave voices out, because in the piano transcription it will sound like there is an extra note if unison voices split up:

Another instance of changes occurring because of voice leading is during the second theme. He actually leaves out a dominant 7th chord (opting for a straight up major chord) – he probably thought it sounded better without the 7th, but it could also have been a voice leading consideration. In the orchestral version, there two contrapuntal lines that are of interest are E – E# – F# and F# – E# – E. The crossing is interesting, but in a piano transcription with limited voice independence, it seems more appropriate to focus on the one that is more interesting. Furthermore, the bass line is moving upwards F# – G# – A#, so Liszt seemed to want to focus on the contrary motion created with F# – E# – E. Again, he might have just left out the dominant chord because it wouldn’t sound good, but I think the underlying reason is the voice leading.

Some changes are more about voicing of chords, where because of the overtones of the piano, it sounds better to have a more open spacing of chords rather than closed. Take for example the left hand here compared to the original cello arpeggios. The difference is small, but the wide spacing sounds better than the closed one on the piano – the broken third in the bass can end up being very muddy.

The timbre of the hands

There is a part of every pianist that wishes their left hand were just as good as their right hand, whether that be control of sound, speed, voicing, or any technical matter. However, I think it is just as well that the hands have their separate character. Liszt thought so, too, because he uses both the visual and aural effect of putting melodies in the left hand. Take for example this second phrase of the opening:

Liszt goes through the trouble of crossing the hands so that the left hand can play the cello melody. Notice later he reverts back, but just the effect of having the melody suddenly be taken up by the left hand is a striking gesture. Not only is it visually interesting, but using the left hand ensures that the melody lies mostly between the thumb, index, and third fingers, which are the easiest fingers to use in terms of weight distribution. This allows for a warmer sound, emulating what the cellos would make.

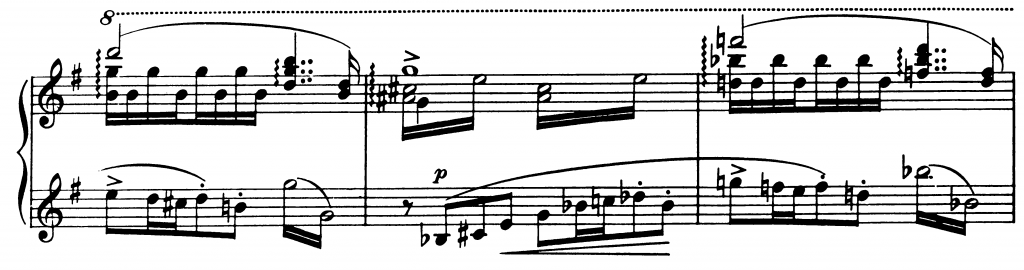

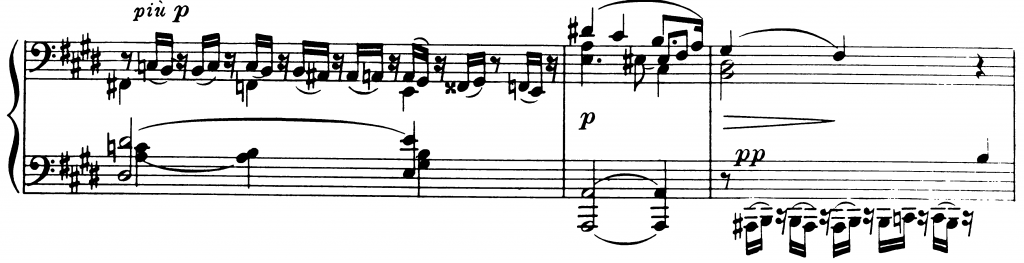

After the fireworks of the first section, the chorale comes back, and Liszt again uses the left hand, this time completely solo, for the first sub-phrase of the main theme. The same effects as the above apply. This also allows the following più p to be even more special, with the addition of the right hand (and thus better control).

Aural Illusion

This isn’t going to be something about Shepard Tones, or weird tritone upwards-downwards ambiguities (which I spent too much time researching than I care to admit), but more about how our brains fill in notes that are omitted, or in different octaves. The closest visual analogy I could find is something like the Kanizsa Triangle, where our brains make a shape out of the negative space. Our brains ability to interpolate is a blessing to transcribers, because often times you just have to leave certain things out.

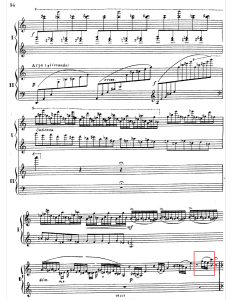

One example is in the very first tutti section, where the right hand has to negotiate the broken descending scales. Here the melody alternates between being in both the right hand and left hand, and just in the left hand; thus, sometimes the melody fills up from the bass to the treble, and other times it only goes up to the tenor. No matter, our brains hear the melody as one line (especially if the pianist voices adequately).

Furthermore, the bass is always omitted when the melody is played, but because we still get an articulated attack, we don’t really miss the bass. As long as it is regularly occurring, our brains assume that the pattern continues.

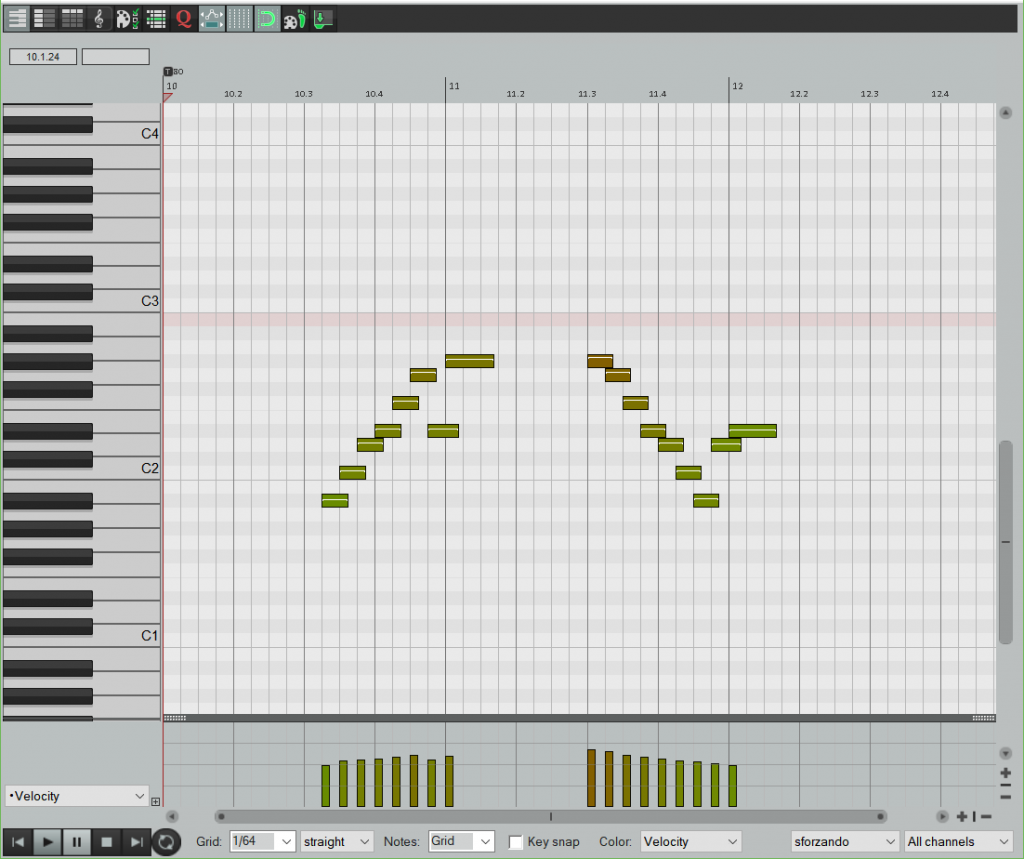

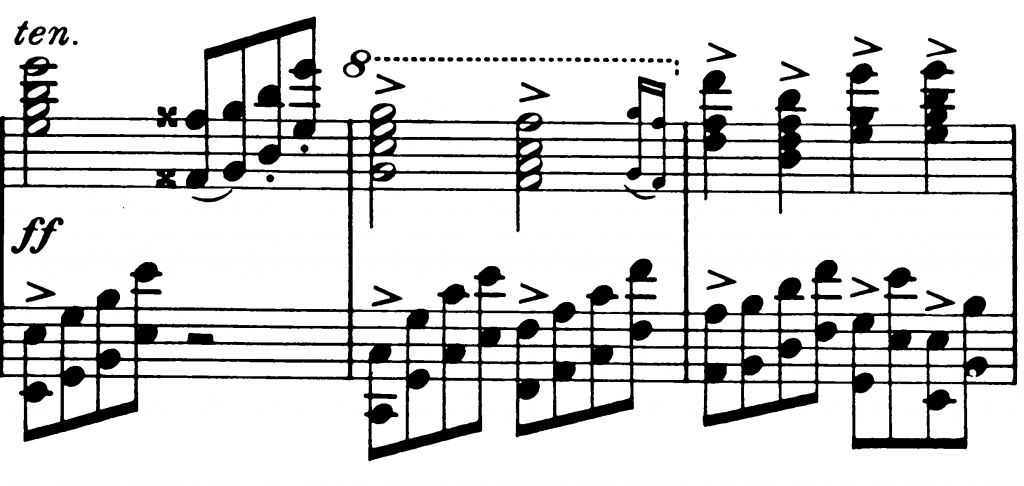

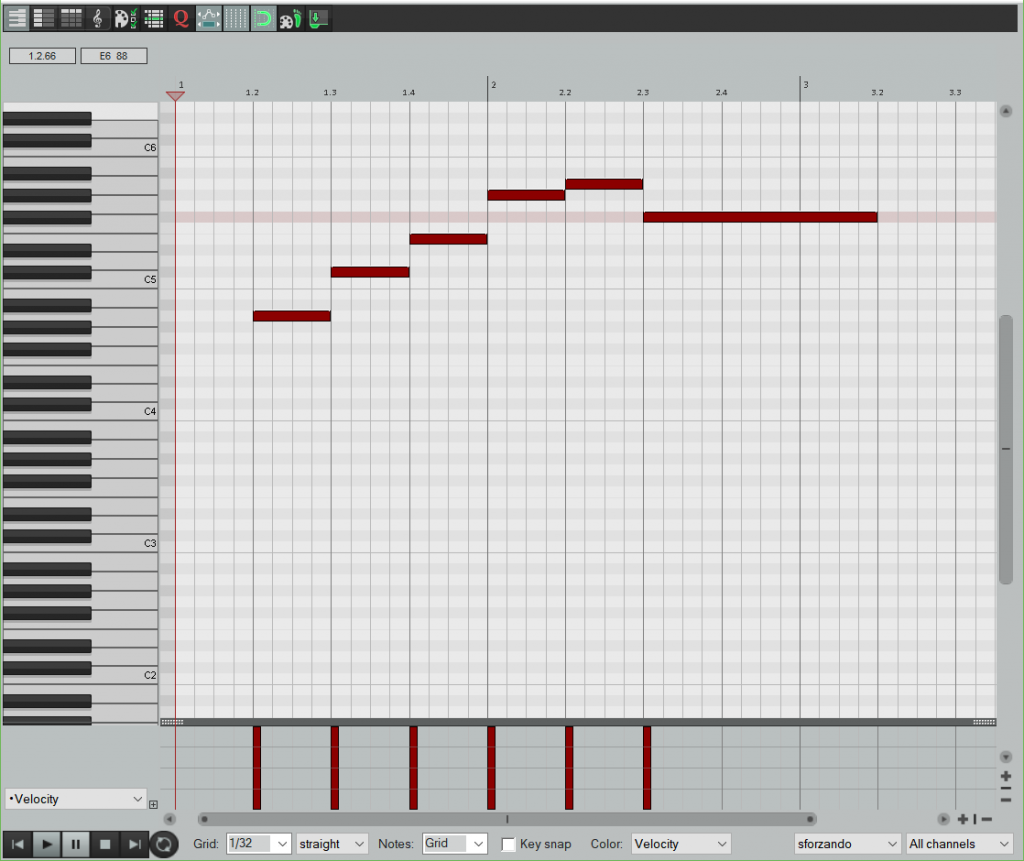

A further striking example is in the main theme of the Allegro – Liszt doesn’t bother to put the melodic high note on the beat. He puts it on the second sixteenth note to make the tremolo pattern easier to play. You can try to come up with alternatives, but none will be as elegant as what Liszt came up with. I think this figuration works because our ears group the first two notes together, so it sounds like a broken downbeat. In fact, we roll and break chords so often in piano music that our ears probably have adjusted to that. It’s really amazing that it sounds better than trying to copy the original rhythm exactly.

Registration

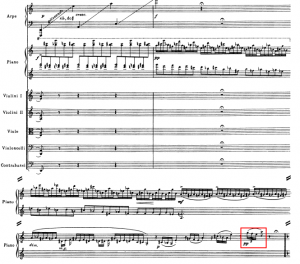

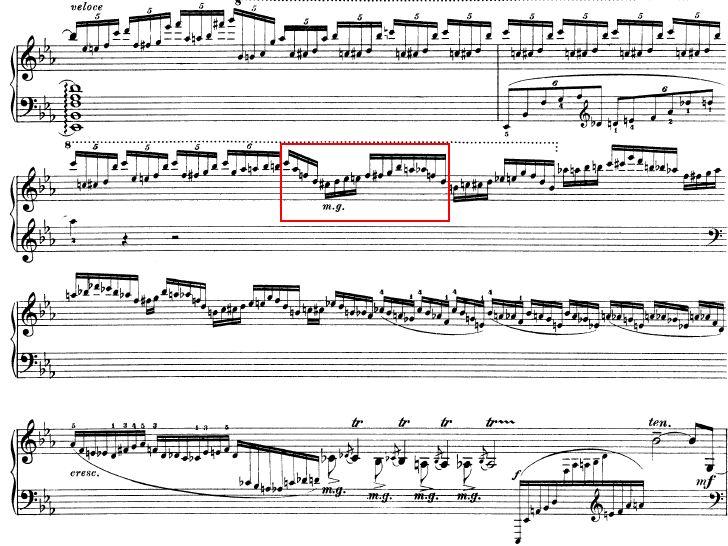

One of the challenges for transcribers is what octave to put notes on the piano. Often we can just put it in the octave that the source is in, but some times that just does not sound quite right. Rather, we must put the notes in the same octave relative to the “normal” range of the instrument. Let’s say there’s a violin passage that’s quite high, like this:

If we put it directly onto the piano, it’s not going to sound as high or stratospheric as the original. In fact, we’re going to have to move it up to another octave so that it has the right sound.

Conversely, this passage in the violins is all the way at the bottom of the G string. Liszt opts to go all the way into the bass clef to convey the timbre of the low violin.

Octave considerations can also apply to whether to put a melody in octaves or unison. Even though two instruments (such as viola and violin) could be playing the same melody in the same octave, the effect is one of rich overtones. Liszt appropriately goes for octaves on this melody.

Making Some Noise

Liszt often gets a lot of flak for putting in runs and chromatic passages as fillers. This piece is no exception, but I do think many of them serve more of a purpose in this piece than others. The orchestral version is loud and full of energy and texture. With only two hands, ten fingers, and two feet, Liszt had to find a way to create the same kind of excitement.

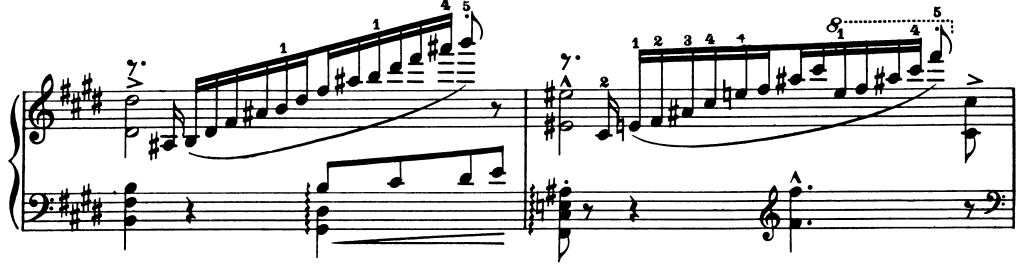

In the transition between the first and second themes, Liszt changes the accompaniment figure from a sextuplet chromatic scale, to sixteenth-note chromatically ascending alternating sixths (whew). This change accomplishes a few things. First, it spans a bit more of the range; Liszt gets to cover a bit more harmonic ground and not have a huge whole between the melody and the bass. Second, it’s a bit easier to play metrically than the polyrhythm – it’s not a hard one, but it can affect stamina and pacing. Third, the rotation of the hand in the oscillating sixths allows for a bigger crescendo.

The beautiful soaring melodies after the second themes are accompanied by brilliant arpeggios. These arpeggios are not in the orchestral score, but they help to get across the effect of this nice legato melody after all of the octave chords previously. It also allows Liszt to showcase the ingenious dividing of the theme between the hands as the right hand climbs up the keyboard over and over again. In addition, the runs make it easier to fill out the harmonic content, since a pianist can’t even begin the span the actual voicing in the original.

“If it ain’t Broke…”

There’s two parts to this topic I want to cover. The first is regarding the relationship between exposition and recapitulation. In the second theme, Wagner changes the orchestration of the accompaniment quite drastically. There’s a bit more scrubbing the second time around, as well as rhythmic diversity (with triplets in the bass). Liszt saw this, thought “well it sounded so good on the piano in the exposition,” and just kept the figurations the same for the recapitulation. I won’t accuse Liszt of being lazy, because let’s face it, the pianist learning the piece is also glad that he or she doesn’t have to learn even more patterns and figurations. However, it’s interesting to think about how it could sound if some of the changes were incorporated into the transcription.

Second is the fact that there is plenty of the piece we didn’t talk about, and that’s because he really didn’t change much from the original source in those parts. The notes are good, and the phrases are good, so Liszt just has to make them fit comfortably in the hands, and he’s good to go. This even applies to that beast of an ending with the flourishing of octaves. There really is no other way that should be transcribed.

However, this is exactly why this piece is so difficult to play. The fact that it is so close to the original version, and that Liszt made very little compromises, especially in the little figurations, means that the pianist really has to be an orchestra. That means singing individual voices, having different colors, filling out the entire dynamic range, and building up the stamina to perform such a work.

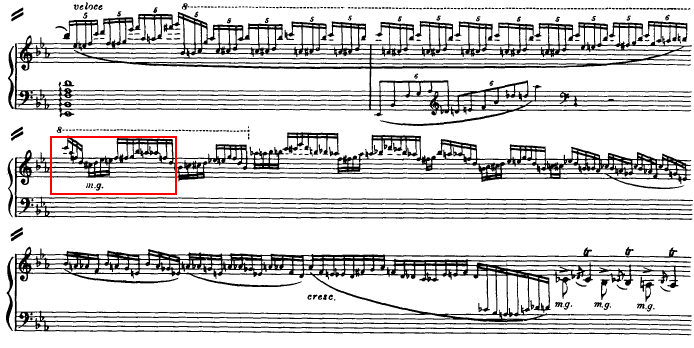

Addendum

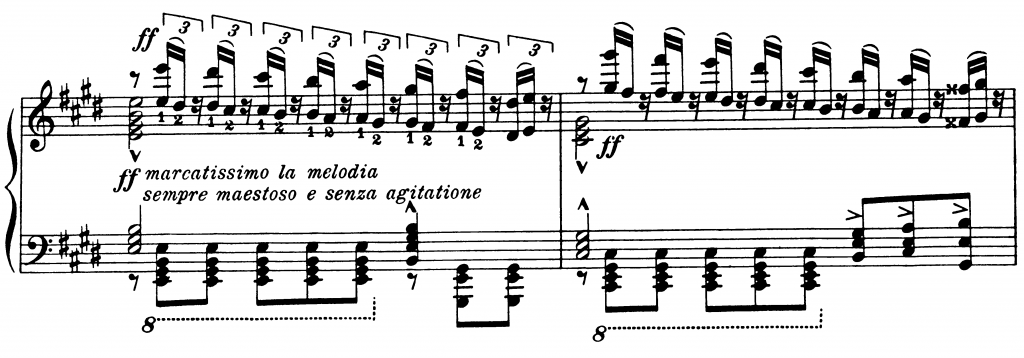

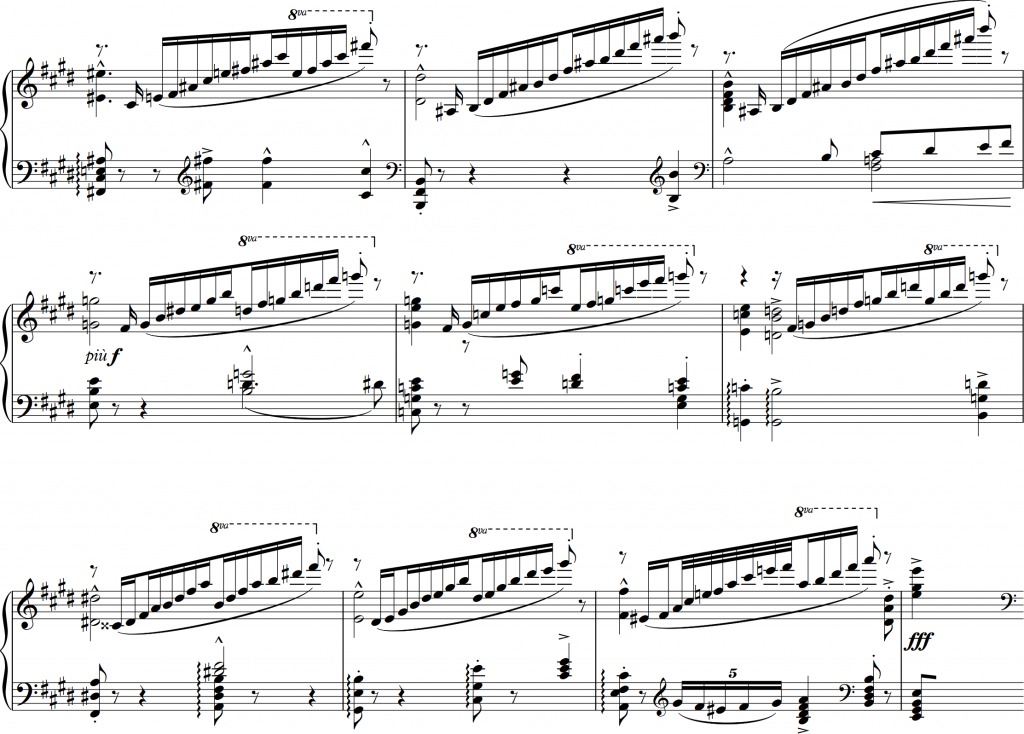

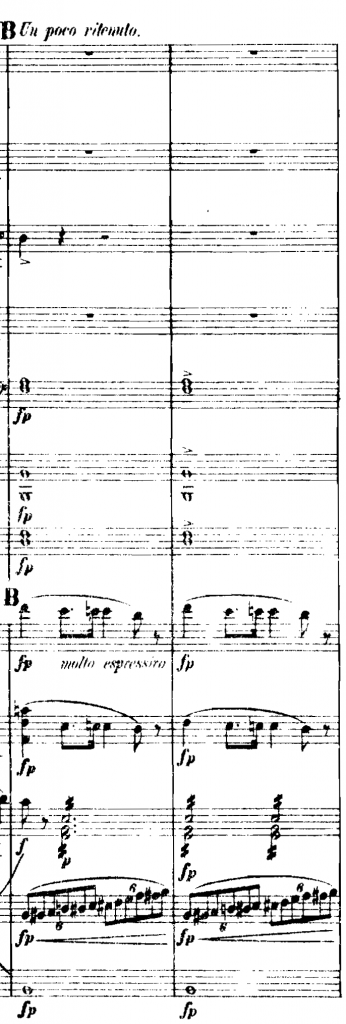

This article wouldn’t be a Sean Chen pianonotes without some re-transcription. As a reward for getting through the entire article, I’ve engraved some of the additions I made to the piece when I performed it. The best part about transcriptions is that you get to hear the piece as the transcriber heard it the original source. Here, we get a glimpse into what Liszt heard when he heard the piece performed live (I assume he did hear it). But, I’m fully of the opinion that if you hear different things, it is okay to add them or change some things in a transcription. You can probably find where these changes should go easily. Without further ado:

Oh boy, this movement… So simple, yet so difficult.

Oh boy, this movement… So simple, yet so difficult.